Daydreams in Music

A math session motivated by patterns in musical scales.

Jeremy Aikin and Cory Johnson

Like the MTCircular? Subscribe to our free semi-annual magazine.

Albert Einstein once said: “If I were not a physicist, I would probably be a musician. I often think in music. I live my daydreams in music. I see my life in terms of music.” There is no shortage of examples of mathematicians and scientists who are also musicians. Perhaps it is the abundance of patterns and structure prevalent in music that underpin these common interests. Such patterns can be seen in the very building blocks of music, which motivated the development of an investigation of musical scales for one of our Inland Empire Math Teachers’ Circle sessions.

A Model of the Piano

In order to study musical scales through the lens of mathematics, we first developed a mathematical model that will allow us to see and to explore the patterns that arise. While musical scales can be played on many different instruments, the piano may be the most natural instrument to use in our investigation since most people know what it looks like and can easily notice patterns when looking at a piano keyboard.

Figure 1. Periodicity of a piano keyboard.

An observer might notice that the piano keyboard seems periodic, repeating the black keys in groups of two and three. Below, we have outlined an example of a single period repeated across the keyboard in blue. In music, such a period is called an octave. This periodicity enables us to restrict our attention to a single octave in our study of musical scales.

We asked the participants, “How many keys are there in Figure 2?” The consensus was twelve.

Figure 2. A single period (or octave).

Then, we asked, “How did you count the keys?” Most of the participants had counted the black keys first, and then counted the white keys. Others had counted all the keys in ascending order. This method of counting allowed us to introduce the idea of ascending order and to define the notion of a half-step (H) and a whole-step (W). A half-step describes the distance between a key on the piano and the neighboring key, in ascending order (for example, from the key labeled 1 to the key labeled 2, or from key 5 to key 6). A whole-step consists of two half-steps (for example, from key 1 to key 3).

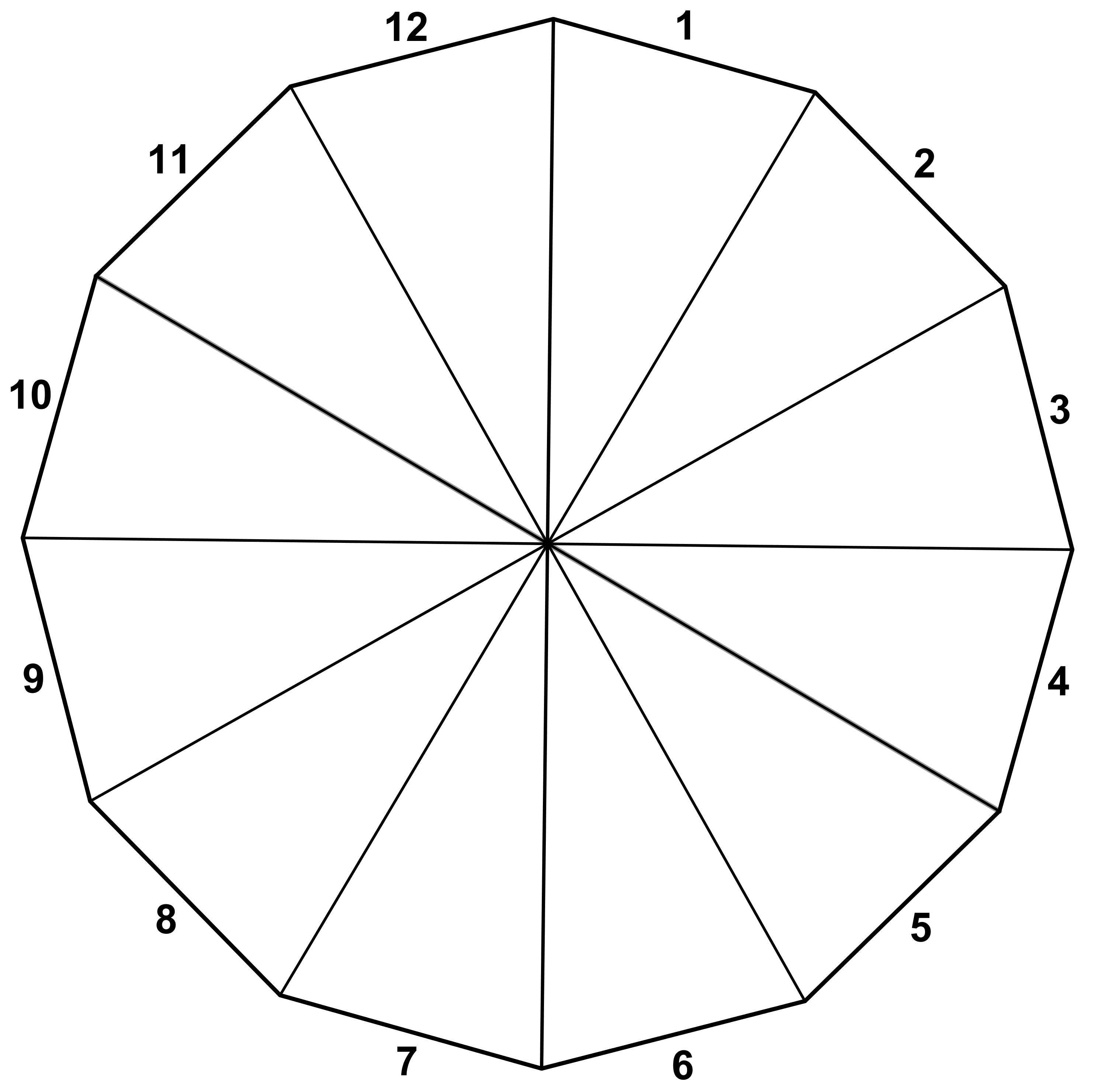

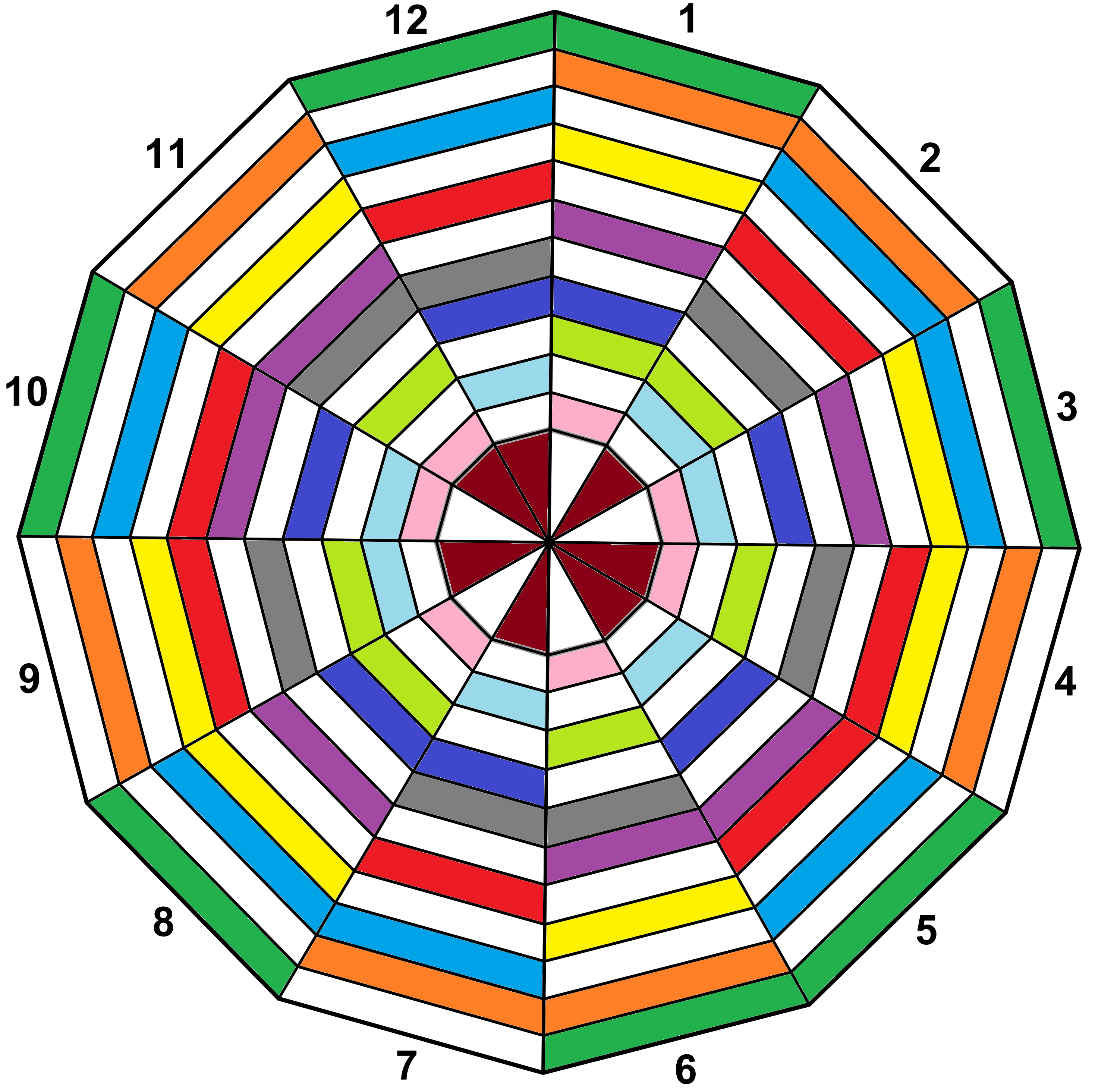

We constructed our model for the piano keyboard by bending Figure 2 into a 12-gon so that keys 1 and 12 became neighboring keys. In the resulting model (see Figure 3 below), adjacent wedges represent one half-step. The numbers that label the wedges in Figure 3 correspond to the numbers that label the piano keys in Figure 2.

Figure 3. A model of a piano keyboard.

Exploring Musical Scales

In music, a scale is broadly defined as a collection of musical notes arranged in order based on the frequencies of their pitches. Scales are often distinguished by the intervals between these pitches, and the intervals involved in building a scale can vary greatly.

For our purposes, we restricted our definition of a musical scale to include only whole-steps and half-steps. We further assumed that a musical scale begins and ends on the same wedge in our model. In music, scales generally begin and end on the same note, but in different octaves. In this sense, each wedge in our model represents an entire class of equivalent notes.

Based on these assumptions, we arrived at the following mathematical definition of a musical scale: A musical scale is a shading of wedges in the model so that given any two neighboring wedges, at least one wedge must be shaded.

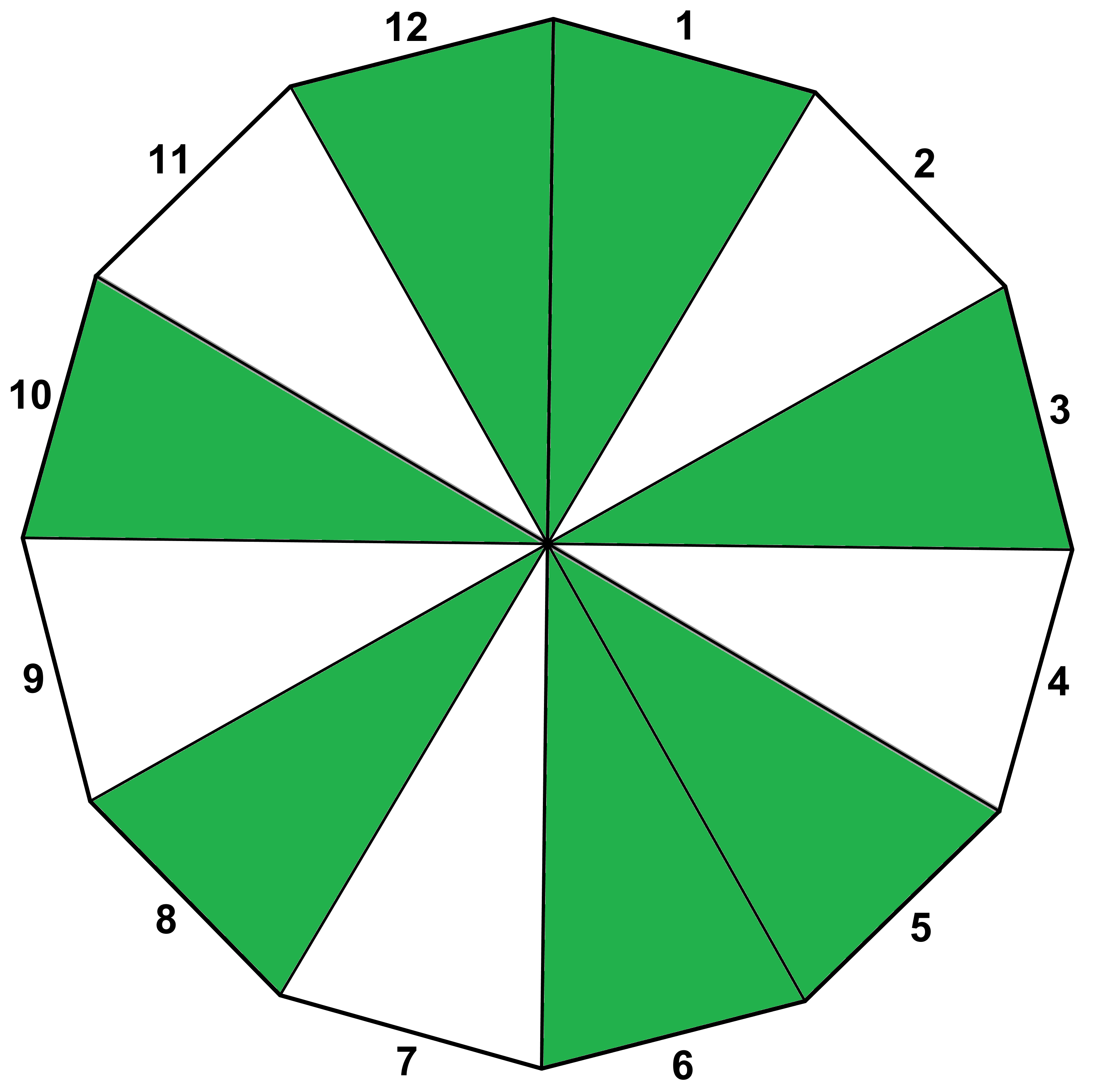

Note that such a shading produces an associated sequence of W’s and H’s. For example, a major scale is the sequence WWHWWWH. Studying the model, if we begin on the wedge labeled 1, the major scale begins by moving a whole-step to wedge 3, a whole-step to wedge 5, a half-step to wedge 6, a whole-step to wedge 8, a whole-step to wedge 10, a whole-step to wedge 12, and then a half-step back to wedge 1. This amounts to playing the white keys on a piano in ascending order (note that if we instead started on wedge 2 and constructed this scale, there would be a mixture of black and white keys played on the piano).

Figure 4. A major scale.

Once we had established our definition of a musical scale, we asked participants when two musical scales might be equivalent, and when they might be considered different.

After some discussion, participants agreed that two musical scales would be equivalent if they consisted of the exact same collection of shaded wedges on our model. Figure 5 shows the scale given by the sequence WWWWWW (in music, this is called a whole-tone scale). Note that if the scale begins on any of the wedges labeled by an odd number, the result is exactly the same collection of wedges. If instead we shade the same sequence on our model beginning on an even labeled wedge, the result is a different collection of wedges. Hence, there seem to be two different types of scales based on this sequence.

Figure 5. A whole-tone scale.

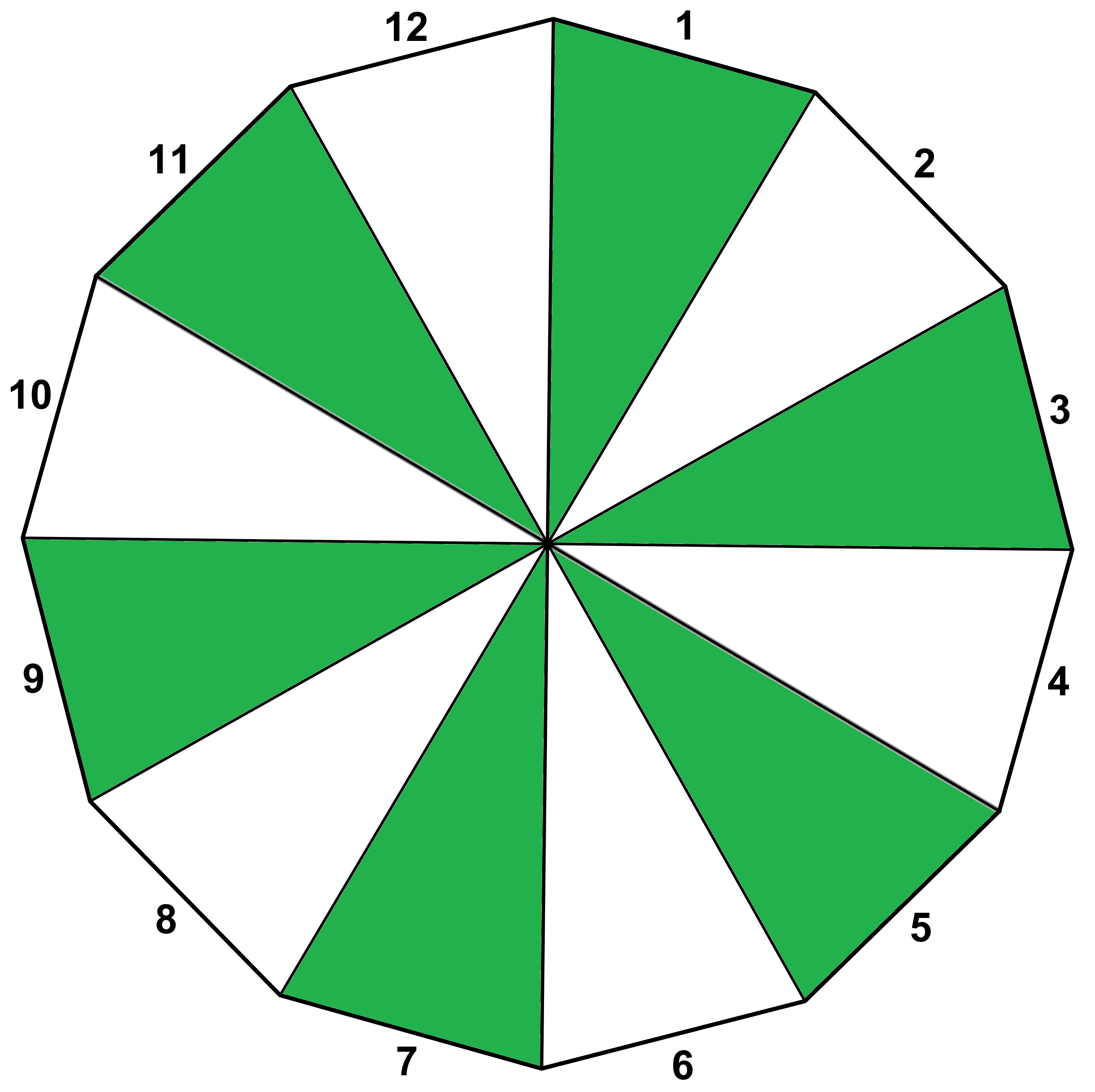

Another interesting case is the diminished scale, represented by the sequence HWHWHWHW (shown in Figure 6). How many different types of scales exist based on this sequence? Our MTC participants noticed that by studying the rotational symmetries of the model for this scale, it was possible to visualize the different types of scales having this sequence. For instance, rotating the diagram clockwise by one wedge, or 30°, resulted in a different collection of shaded wedges. However, rotating clockwise by three wedges, or 90°, gave us the same collection of wedges as our initial configuration.

Figure 6. A diminished scale.

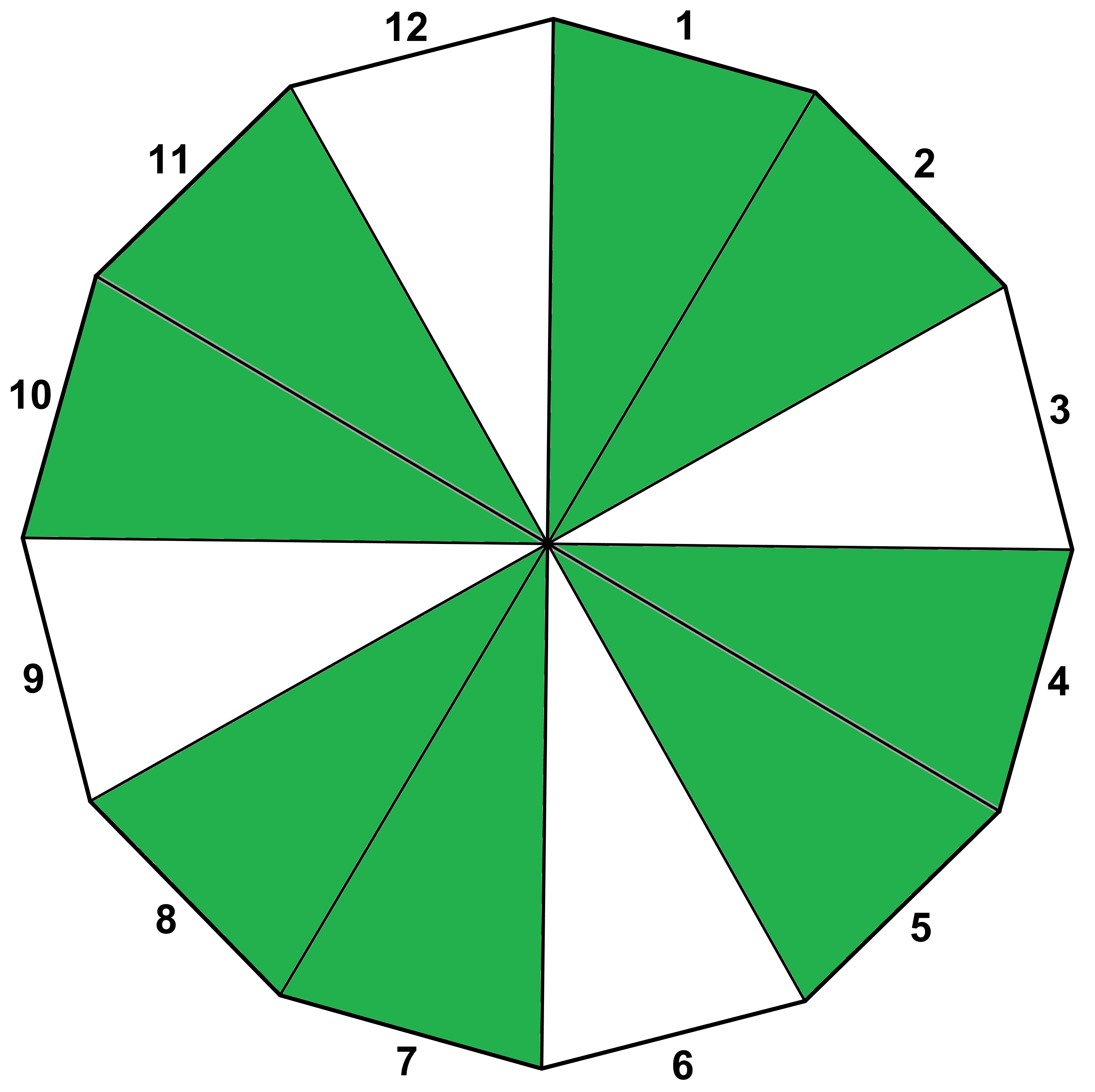

We concluded that there must be three different types of scales having the sequence HWHWHWHW. Could the same idea be used to determine the number of different types of major scales (WWHWWWH)?

We asked the participants to create their own musical scale by shading a collection of wedges on the model, using only whole and half-steps. This was the most exciting part of this session. From the diagram, they could produce a sequence of W’s and H’s. By analyzing the rotational symmetries, they were able to determine how many different types of scales could be produced having that sequence.

By subdividing the keys in our model, we can keep track of rotational symmetries. This figure shows that there are 12 different major scales.

Figure 7. All 12 major scales.

We asked a natural follow-up question: Is it possible to create musical scales having exactly four different types? More generally, is it possible to create musical scales in which there are exactly five, six, seven, or eight different types? A challenging combinatorial question is: How many different musical scales can our model produce?

Extensions

A nice way to extend this problem would be to consider altering our definition of a musical scale to include other intervals, such as a “three-halves-step” (T). This definition might be stated as follows: A musical scale is a shading of wedges in the model so that given any three consecutive wedges, at least one wedge must be shaded. For example, shading the wedges in our model that are numbered 1, 4, 6, 7, 8, 11 yields the sequence TWHHTW and results in a scale that in music is commonly referred to as a blues scale. Changing the definition creates new scales and allows one to extend the analysis of rotational symmetries.

Reflection

The exploration of musical scales was an engaging session that was accessible to elementary and secondary teachers with and without a musical background. After constructing the model of the piano keyboard, teachers needed minimal instruction from the facilitators. The questions generated were thought-provoking and left room to expand to a deeper level of thinking. As a bonus, we brought in a portable keyboard and played the scales created by our attendees. This brought the session to life in a wonderful way, and enabled us to hear the product of our mathematical thinking.

Resources

- Blank templates of the piano model:

This article originally appeared in the Summer/Autumn 2017 MTCircular.

|

|

Jeremy Aikin and Cory Johnson are both assistant professors of mathematics at California State University, San Bernardino. They are co-leaders of the Inland Empire Math Teachers’ Circle, which is a member of the Southern California MTC Network. |

MORE FROM THE

SUMMER/AUTUMN 2017 MTCIRCULAR

|

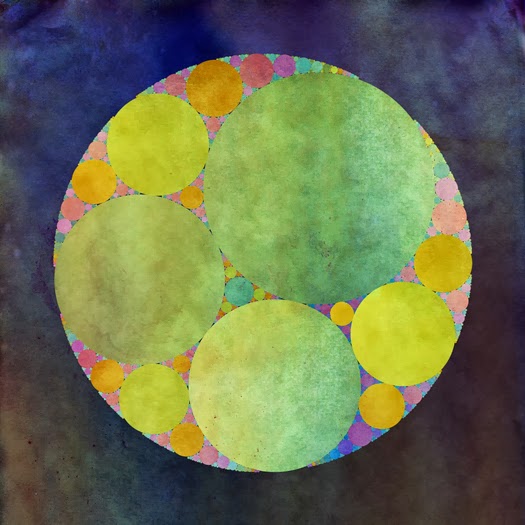

A Problem Fit for a PrincessApollonian gaskets in history

|

|

What’s in a Logo?A sampling of logos from MTCs across the country

|

|

Polygons and PrejudiceIntroducing social issues through math

|

|

Problem PosingA framework to empower participants

|

|

MTCs featured in KQED MindShiftKQED News reports that Math Teachers’ Circles help teachers bring a sense of wonder and discovery back to math classrooms

|

|

MTCs Advocating for Math in ESSA PlansUndertaking a collaborative effort to promote the advancement of mathematics education

|

|

Adams, Ghosh Hajra, Manes Win AwardsThree MTC leaders recognized for teaching excellence and community engagement

|

|

A Note from AIM: #playwithmathCelebrating math as social, creative, and energizing

|

|

Dispatches from the CirclesLocal updates from across the country

|

|

Global Math WeekComing in October!

|